What makes complex problems complex? Obviously, it’s their messy and unpredictable side. However, when we start examining it by posing the right questions and finding the answers – we’re already halfway there.

In this part-two conversation with Dr. Irene Glendinning we’re ruminating on who takes bigger responsibility in fighting academic dishonesty cases as well as the reasons pushing students to search for shortcuts.

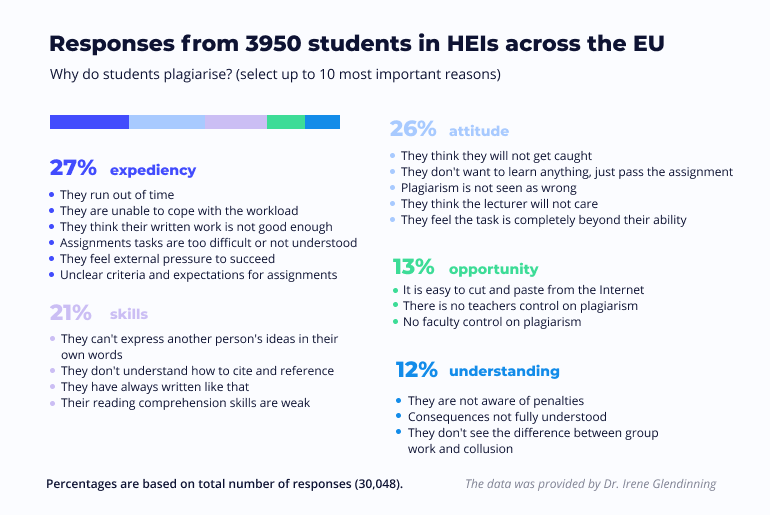

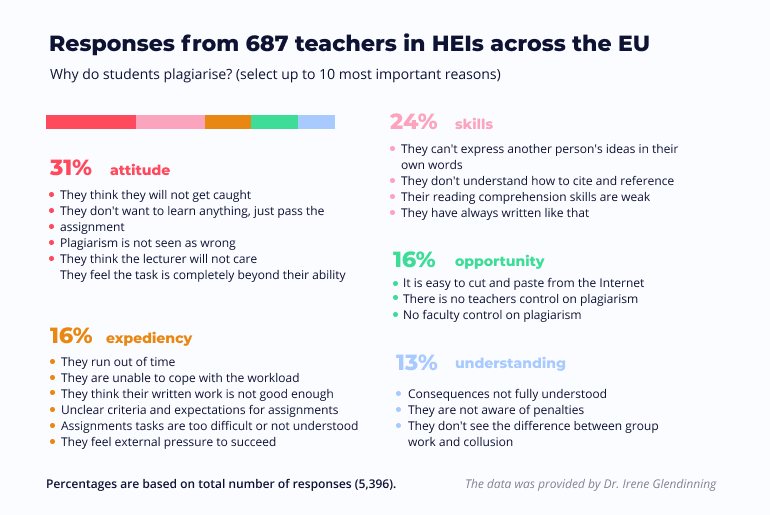

Starting with the project Impact of Policies for Plagiarism, Higher Education Across Europe (IPPHEAE 2010-2013), followed by two subsequent projects, South East European Project on Policies for Academic Integrity (2016-17) and more recently Project on Academic Integrity in Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, Kazakhstan and Turkey (2018-19), Dr. Irene Glendinning, together with colleagues and partners, collected data from higher educational institutions operating in 38 countries in Europe and Eurasia. The most curious part was–students and teachers’ responses to “Why do students plagiarise?”.

The research findings contain invaluable information that can spark a thought on what else could be done to improve the quality of education and hands-on skills acquired by students.

Jump to the interview to get a broader view of the issue.

Unicheck: Many educators agree that plagiarism signals the gaps in the educational process. Who takes the biggest responsibility for bridging them: an academic institution or an educator?

Irene: It is everyone’s responsibility to address plagiarism, accidental and deliberate, as well as other forms of academic dishonesty, including the students themselves.

There is a serious need for education to ensure all students coming to HE, at any level, develop the necessary skills to successfully complete their programme over the whole of their study time. If students don’t understand how to write in an academic style or how and why to make use of literature sources, then they are very likely to plagiarise inadvertently.

Educators around the world often underestimate how long it takes for students to learn to write well. For all sorts of reasons, it is no good just giving an hour on referencing when students first arrive and assuming they’ve “covered it”.

I’m still learning how to write after more years than I care to tell you about. It is complex and time-consuming to learn how to paraphrase well, build an argument etc., particularly for students who come from an exam-based assessment regime and those writing in another language.

On deliberate cheating, if there are no consequences and students believe that everyone else is getting away with it, then some students will be tempted to push their luck. There needs to be a very transparent institution-wide approach to deterring academic dishonesty that is consistently and fairly implemented. To make that work requires resources and leadership. The whole academic community needs to appreciate the need for integrity and their role in helping to reduce academic dishonesty. That includes how assessment is designed and delivered as well as having robust policies for detecting and deterring misconduct.

It is worth pointing out that governments, education ministries and quality assurance bodies have a key leadership role in encouraging institutions to take steps to safeguard their quality, standards and integrity. Ideally not just in higher education, but starting much earlier in education.

Unicheck: In the IPPHEAE study, you surveyed 27 countries (more than 100 academic institutions) and the policies preventing plagiarism they had in place. Which of them showed the biggest efficacy and why?

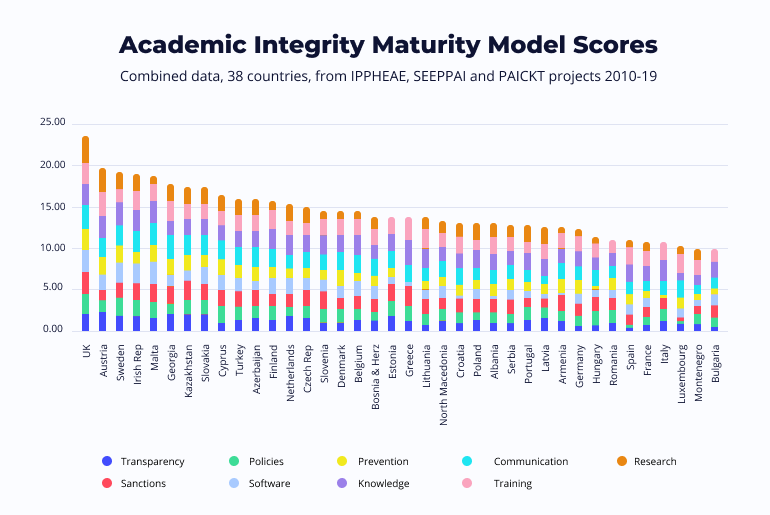

Irene: We have actually surveyed 38 countries now through 3 separate projects between 2011 and 2019. Here’s the chart with a summary of our findings:

The UK has the highest overall score – just over 24/36 on the Academic Integrity Maturity Model (AIMM), but closely followed by Austria and Sweden. However, the data for the 27 EU countries (initially without Croatia – joined EU in 2013) was collected 2011-2014 and it is likely we’d get different results if we ran it again now.

The countries that scored highest have been working systematically with nationally agreed frameworks and standards, requiring compliance on higher education quality assurance, standards and integrity. Other countries we surveyed more recently are developing their strategies, notably Georgia, Montenegro, Kazakhstan, but I believe it is still the case that of the 38 countries surveyed so far, no country has an approach to academic integrity as effective, embedded and established as the UK, because it is taken seriously across the whole HE sector these days. Even UK institutions that did not have strong policies in 2012 are now doing a lot more.

Unicheck: What were the major reasons for academic dishonesty based on the answers received from the students and educators you surveyed? How did their viewpoints differ?

Unicheck: What were the major reasons for academic dishonesty based on the answers received from the students and educators you surveyed? How did their viewpoints differ?

Irene: There were many different reasons given for academic dishonesty and the reasons varied depending on who we asked, varied on country and also views of teachers compared to students.

The top reason for teachers and students overall was “easy to cut and paste”, for students the second most popular was “run out of time” and then “think they will not get caught”. A mixture of expediency, attitude, skills, opportunity and understanding.

Unicheck: EdTech companies contribute to raising academic integrity at academic institutions deploying various innovative technologies. What is the role of technologies in fighting academic dishonesty?

Unicheck: EdTech companies contribute to raising academic integrity at academic institutions deploying various innovative technologies. What is the role of technologies in fighting academic dishonesty?

Irene: Technological solutions are not a silver bullet, but if they can help to strengthen the evidence and save staff time in generating good quality evidence, then genuine cases are more likely to be proven.

If students know we are more likely than not to detect contract cheating many students will be dissuaded from going down that path.

However, we must remember that contract cheating is not just about essay mills, it also can involve other students or friends and relatives doing the work for them. All are equally wrong. Even if we succeed in putting essay mills out of business, the problem will still be there.